Introduction

Materials and Methods

Asparagus cultivation and preparation of the spear extract

Determination of the rutin content

Determination of anti-cancer activity

Anti-obesity effect test

Statistical Analysis

Results and Discussion

Rutin content

Anti-cancer activity

Anti-obesity effect

Conclusion

Introduction

Vegetables contain macromolecular and micromolecular nutrients necessary for a well-balanced diet and for human health maintenance (Dias, 2012; Zhu et al., 2018). The consumption of vegetables has been demonstrated to prevent and treat various diseases (Trigueros et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2015; Laura et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2019; Akhtar et al., 2020). Asparagus, Asparagus officinalis L., is considered to be one of the most valuable vegetables owing to its potential sensory properties and high nutritional value (Drinkwater et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2020). Asparagus spears contain carbohydrate, protein, dietary fiber, vitamins, β-carotene, and minerals (Chitrakar et al., 2019; Pegiou et al., 2019). In addition, asparagus spears are rich in phenolic compounds and steroidal saponins, which are good for consumers (Lee et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2020). The dominant phenolic components of asparagus spears are rutin, quercetin, and phenolic acids (Lee et al., 2014; Siomos, 2018; Guo et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2022a). Bioactive compounds present in asparagus spears exhibit anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, and anti-obesity activities, as well as immunomodulatory effects (Ku et al., 2018a; Guo et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2022a).

Asparagus is cultivated in many countries around the world (Guo et al., 2020). The phytochemical compounds in asparagus spears depend on many factors (Ku et al., 2018b; Siomos, 2018; Eum et al., 2020). Besides environmental factors, the asparagus cultivar is an important factor affecting the phenolic content in spears (Papoulias et al., 2009; Cao et al., 2022b). Among male asparagus cultivars, the Jersey Giant, Jersey Supreme, and NJ953 cultivars can potentially be cultivated in certain countries due to their high spear productivity (Elmer et al., 1997; Benson, 2001; Drost, 2001; Motoki et al., 2005; González, 2009). However, UC157, a male-female mixed cultivar, is popular in Japan and Korea owing to its high spear yield (Haihong et al., 2017; Shawon et al., 2021). In addition, cladophylls and spears grown in the open fields have a higher content of rutin than those grown in closed systems (Motoki et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2022a). In addition, the rutin and protodioscin contents differed between the tip and basal region of cladophylls (Motoki et al., 2012). To date, comparison of the rutin content, anti-cancer activity and anti-obesity effect of Jersey Giant, Jersey Supreme, NJ953, and UC157 asparagus cultivars are scant. Therefore, the objective of the current study is to compare the rutin content, anti-cancer activity and anti-obesity activity of these four cultivars.

Materials and Methods

Asparagus cultivation and preparation of the spear extract

Three male asparagus (Asparagus officinalis L.) cultivars (Jersey Giant, Jersey Supreme, and NJ953) and the male-female mixed cultivar UC157 were used in this study. Asparagus seeds were immersed in water for 2 h and then sown into 50-hole plug trays using vermiculite. Five weeks after sowing, seedlings with similar plant height and shoot number were selected and transplanted into plastic pots (12×11.5 cm) containing a growth medium (Alpha Plus, Sanglim, Korea). The asparagus plants were watered every 2–3 days to prevent the topsoil from drying out.

Before transplanting the asparagus plants at 11 months, chemical fertilizers including 80 kg of horticultural complex fertilizer (nitrogen 12%, soluble phosphoric acid 7%, soluble potassium 9%, soluble magnesium 2%, and soluble boron 0.2%), 100 kg of lime, and 1.5 kg of borax were supplied into 330 m2 of the soil. After the soil in the open field was treated with 2 kg of soil insecticide and mulched with black film, 11-month-old asparagus plants were planted in beds at 180 × 30 cm intervals. The asparagus was cultivated in the open field at Wonkwang University Botanic Park. The spears were harvested from March to April when the plant age was 21 months.

After harvesting, the spears were stored in a freezer (ULT Freezer, Thermo Fisher Scientific Korea, Seoul, Korea) at ‒70°C, lyophilized using a freeze dryer (OPERON, Kimpo, Korea) for more than 48 h, and then powdered using a pestle and mortar. The bioactive compounds in the spear powder (0.1 g) were extracted with 70% methanol (1 mL). The extraction was performed at 30°C in a shaking thermostat incubator (KMC-1205 SWI, Vision Co., Korea) for 24 h. The supernatant was collected by centrifuging the extraction dispersion at 13,000 rpm for 10 min and filtering through 0.22 µm syringe filter to remove insoluble materials.

Determination of the rutin content

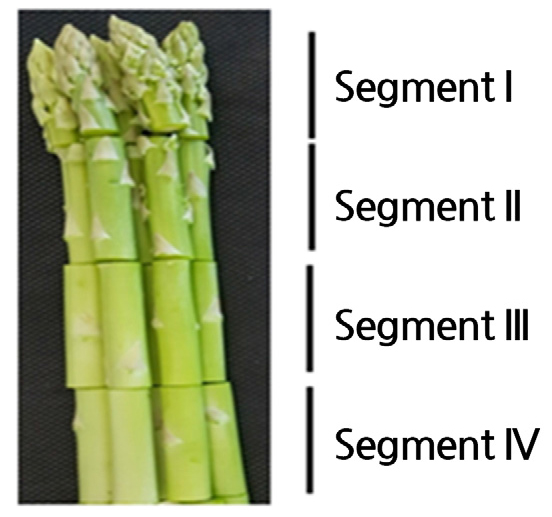

The harvested spears (20 cm in length) were cut into 4 segments with an equal length of 5 cm per segment. Segments I, II, III, and IV were labeled from the tip to the basal region of the spears in order (Fig. 1). A prominence high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used to determine the rutin content in each segment of the spears. A C18 column (0.46×2.5 cm, particle size 5 µm; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and a diode array UV-VIS detector (SPD-20A VWD, Shimadzu) were included on the system. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (water), solvent B (acetonitrile; Daejung, Siheung, Korea), and 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. Its flow rate was 0.7 mL/min. The gradient program involved an increase in solvent B from 12% to 30% at 20 min, to 80% at 50 min, with maintenance at 80% until 53 min. Subsequently, solvent B decreased to 12% at 54 min and was maintained until 60 min. The injected volume of the spear extract was 10 µL. The column temperature was at 40°C. Rutin hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as standard for the rutin content analysis. The analysis wavelength was 280–330 nm.

Determination of anti-cancer activity

The MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliumbromide] assay was conducted to determine the anti-cancer activity of the four asparagus cultivars. Human MCF-7 breast cancer cells, HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells, and Calu-6 lung cancer cells were obtained from the Korean Cell Bank. The cancer cells were aliquoted into 96-well plates and cultured in an incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for 24 h. The cultured cancer cells were treated with 10 µL of the spear extract at concentrations from 50 to 800 µg·mL-1 and incubated for 24 h. Each well was added with 10 µL of MTT solution (0.2 mg·mL-1) and subsequently incubated for 4 h. The DMSO (100 µL) was added to the wells after the removal of the supernatant. The incubation process lasted for 10 min and was conducted at room temperature. The absorbance was determined at 540 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The viability of the treated cells was expressed as a percentage of that of the untreated cells.

Anti-obesity effect test

For the anti-obesity effect test of the four asparagus cultivars, 3T3-L1 cells (KCLB No. 10092.1) from the Korea Cell Line Bank were used. The 3T3-L1 cells are preadipocytes that differentiate and form fat tissue under favorable conditions (Ntambi and Kim, 2000).

Cytotoxicity measurement

The MTT method was used to measure the adipocyte viability (Sladowski et al., 1993). The cultured 3T3-L1 cells were aliquoted in a 96-well plate at 1×105 cells per well, incubated for 16–18 h and then treated with spear extracts from the four cultivars, at a concentration of 50–800 µg·mL-1 for approximately 24 h. Subsequently, 10 µL of 5 mg·mL-1 MTT was added to 990 µL of medium in the well. The well incubation was performed in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for a further 3 h. DMSO (200 µL) was added to each well, followed by stirring for 20 min after the removal of the culture medium. Absorbance measurements were taken at 595 nm using an ELISA reader.

Oil red O staining

To fix the cells after discarding the cell culture medium, 50 µL of 10% formaldehyde was administered to each well and each was then incubated at 4°C for 1 h. The adipocytes were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline after the formaldehyde was discarded. The staining solution was prepared by dissolving 0.25 g of Oil red O in 50 mL of isopropyl alcohol and mixing with distilled water at a ratio of 3:2, and filtering through a 0.45 µm filter. After addition of 500 µL of DMF and restraining at room temperature for 1 h, the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline. The stained cells were visualized under a microscope and after observation, the dye staining in the adipocytes was extracted with 500 µL of isopropyl alcohol per well. A spectrophotometer was used to measure the absorbance at 520 nm.

Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the obtained data. Significant differences between treatments were analyzed using Duncan's multiple range test at p < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Rutin content

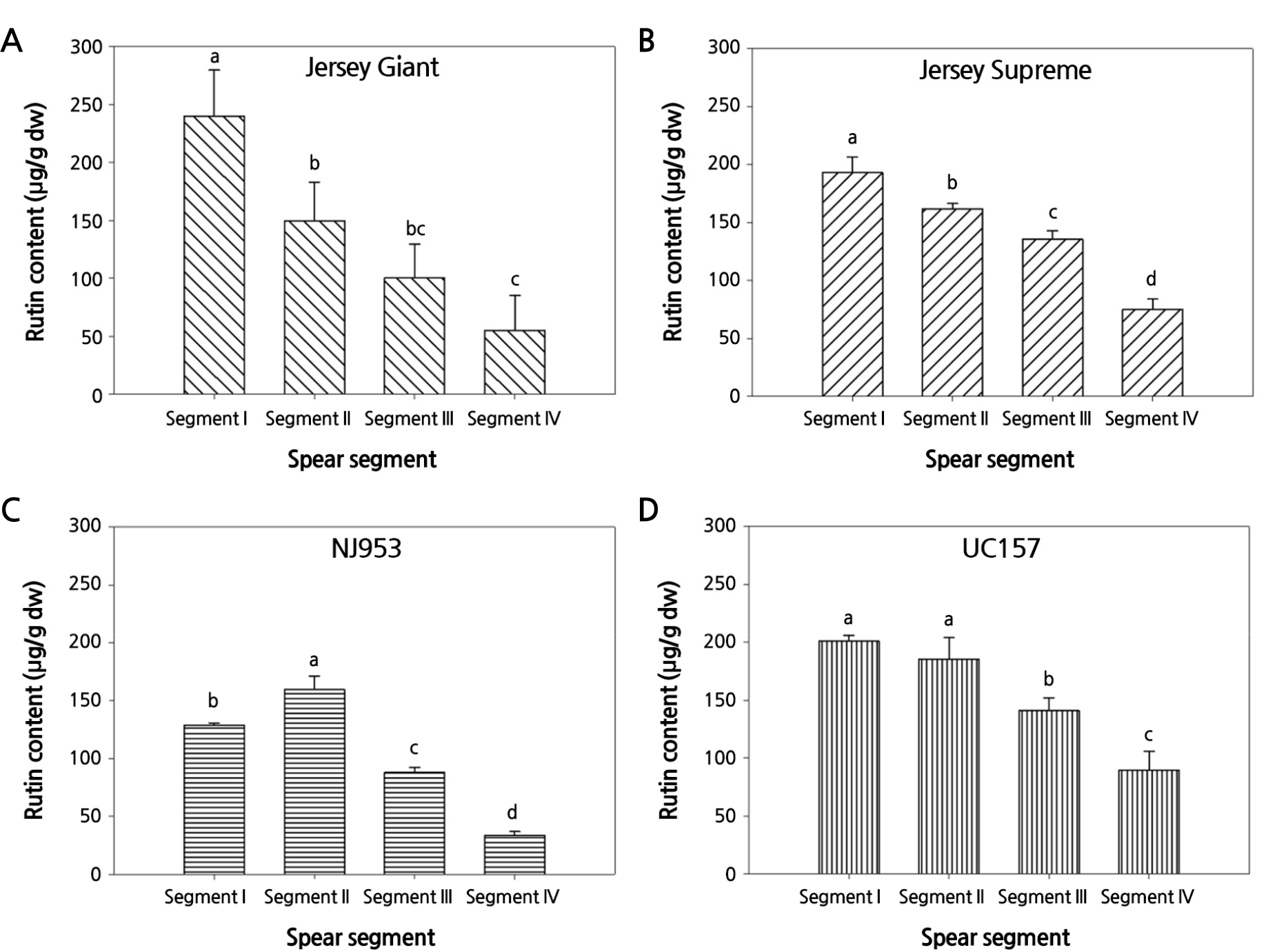

The rutin contents in different spear segments of the four cultivars were compared (Fig. 2). In the Jersey Giant and Jersey Supreme spears, the rutin content decreased gradually from the tip (segment I) to the basal region (segment IV) (Fig. 2A and 2B). In the NJ953 and UC157 spears, the highest two segments from the tip (segments I and II) had the highest content of rutin; the rutin content then decreased gradually from segment II at the middle to segment IV at the base of the spears (Fig. 2C and 2D). The decrease in the rutin content from the spear tip to the basal region in the four examined cultivars is attributable to differences in the exposure to sunlight of the plants. It was reported that exposure to sunlight stimulated the synthesis of phenolic compounds, including rutin (Siomos, 2018; Cao et al., 2022a). The tips of the spears may be fully exposed to sunlight, whereas the basal segments of the spears may be shaded by the ferns of the plants. Differences in exposure to sunlight between the tip and basal segments may result in differences in the activation or inhibition of enzymes, synthesizing or degrading the phenolic compounds in the spear segments (Eichholz et al., 2012; Huyskens-Keil et al., 2020). The results were in agreement with those from other studies (Wang et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2010).

In segment I, the rutin content of the Jersey Giant cultivar was not significantly different from that of the UC157 cultivar; however, it was higher than that of the Jersey Supreme and NJ953 cultivars (Fig. 2). The rutin content in segment II was not significantly different among the four cultivars, whereas the rutin contents in segments III and IV of the Jersey Supreme and UC157 cultivars were significantly higher than those in the basal segments of the Jersey Giant and NJ953 cultivars.

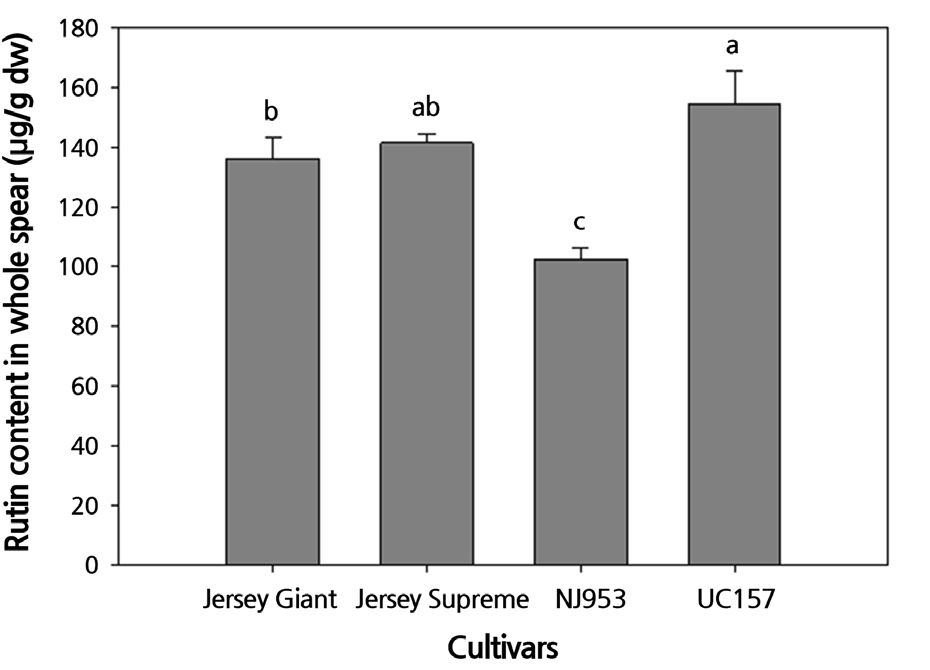

The rutin content in the whole spear of the four cultivars was as follows in descending order: UC157 ≥ Jersey Supreme ≥ Jersey Giant > NJ953 (Fig. 3). The rutin content in the whole spears of the UC157 cultivar was significantly higher than that in the Jersey Giant and NJ953 spears, but not significantly different from that in the Jersey Supreme spears.

Anti-cancer activity

Extracts from asparagus spears of the four cultivars exhibited anti-cancer activity against Calu-6 lung, HCT-116 colorectal, and MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Table 1). At spear extract concentrations from 50–800 µg·mL-1, the anti-cancer activity against HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells was higher than that of Calu-6 lung and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. At the 50 µg·mL-1 concentration of spear extract, the viability of HCT-116 cancer cells incubated with the Jersey Supreme cultivar was higher than that of the cells incubated with the other three cultivars, implying that the anti-cancer activity of Jersey Supreme against HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells was lower than that of the other three cultivars. At extract concentrations from 100–800 µg·mL-1, the UC157 cultivar was more effective at reducing the number of viable HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells compared to the Jersey Giant and Jersey Supreme cultivars, indicating that the UC157 cultivar had higher anti-cancer activity against HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells. There was no significant difference in the anti-cancer activity against HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells between the NJ953 and UC157 cultivars, except at the concentration of 200 µg·mL-1. In 2008, colorectal cancer was the third most common cancer in the world (Alonso-Castro et al., 2013). In this study and in previous studies, rutin was found to be an abundant flavonoid compound present in asparagus spears (Cao et al., 2022a). Rutin was found to exhibit cytotoxic effects on colorectal cancer cells (SW-480) with IC50 values of 125 mM, without exhibiting cytotoxicity against non-tumorigenic cells (Alonso-Castro et al., 2013). In addition, the consumption of rutin effectively decreased the weight and volume of colorectal cancer tumors in mice bearing SW-480 cells, without decreasing other relative organ and body weights of the mice, and it increased the life spans of these mice (Alonso-Castro et al., 2013). Therefore, consumption of asparagus containing rutin and other phenolic compounds may prevent and reduce colorectal cancer in humans (Bousserouel et al., 2013). In addition, asparagus extract containing safe bioactive compounds can be used to treat colorectal cancer due to its anti-tumor activity and low toxicity against non-tumorigenic cells (Alonso-Castro et al., 2013; Bousserouel et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Viability of cancer cells treated with spear extracts of the four asparagus cultivars grown in the open field at 21-month-old plants

|

Cultivar (A) | Cell Viability, % of control | ||||||||||||||||||

| Spear extract concentrations (µg·mL-1) (B) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 50 | 100 | 200 | 400 | 800 | |||||||||||||||

| Calu-6 | HCT-116 | MCF-7 | Calu-6 | HCT-116 | MCF-7 | Calu-6 | HCT-116 | MCF-7 | Calu-6 | HCT-116 | MCF-7 | Calu-6 | HCT-116 | MCF-7 | |||||

|

Jersey Giant | 86.23z aby | 49.42 b | 70.76 a | 88.98 a | 50.19 a | 71.12 a | 81.60 a | 46.09 ab | 68.92 b | 52.31 b | 46.65 a | 66.37 b | 51.56 b | 40.61 a | 64.48 a | ||||

|

Jersey Supreme | 83.06 ab | 58.02 a | 83.88 a | 82.32 ab | 48.88 a | 82.40 a | 74.29 a | 47.49 a | 82.52 a | 68.85 a | 40.42 a | 77.29 a | 66.99 a | 36.71 a | 68.64 a | ||||

| NJ953 | 93.04 a | 50.94 b | 78.00 a | 82.61 ab | 45.92 ab | 75.19 a | 78.26 a | 41.11 b | 74.90 b | 75.40 a | 39.80 ab | 73.23 ab | 65.71 a | 33.78 bc | 70.00 a | ||||

| UC157 | 79.80 b | 46.20 b | 81.42 a | 79.47 b | 41.52 b | 79.36 a | 72.99 a | 35.90 c | 74.16 b | 72.66 a | 33.24 b | 74.93 ab | 68.82 a | 32.36 c | 71.43 a | ||||

| A | nsx | ns | * | ** | ns | ||||||||||||||

| B | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||||||||||||||

| A×B | ns | ns | * | *** | ** | ||||||||||||||

The anti-cancer activity against Calu-6 lung cancer cells of the Jersey Giant cultivar was not significant different from that of the other three cultivars when the concentration of the extract used for incubation of Calu-6 lung cancer cells was at 50 and 200 µg·mL-1 (Table 1). However, this activity was significantly higher in Jersey Giant than that of the other three cultivars when Calu-6 lung cancer cells were incubated with 400 and 800 µg·mL-1 of the extract, as a result of the significantly lower viability of Calu-6 lung cancer cells incubated with the Jersey Giant extract compared to those treated with extracts from the other three cultivars. Lung cancer is a common human cancer with high incidence and mortality worldwide (Aksorn and Chanvorachote, 2019; Muller et al., 2019). Flavonoid compounds in plants have exhibited anti-cancer activity by inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and inducing cancer cell apoptosis (Muller et al., 2019; Abotaleb et al., 2020).

A significant effect of the asparagus extract to the viability of MCF-7 breast cancer cell was observed (Table 1). The MCF-7 breast cancer cell viability decreased by 16.12–35.52% after incubation with the spear extract at all concentrations compared to the control sample. At spear extract concentrations of 50–100 µg·mL-1 and 800 µg·mL-1, the anti-cancer activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells was not significantly different among the four cultivars. At spear extract concentration of 200 µg·mL-1, the viability of MCF-7 breast cancer cells incubated with Jersey Supreme extract was higher than that of the cells incubated with the other three cultivars. Therefore, the anti-cancer activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells of the Jersey Supreme cultivar was lower than that of the other three cultivars.

Breast cancer is a common cancer occurring in women worldwide (Selvakumar et al., 2020). It has been demonstrated that obesity, the consumption of unhealthy food, and lack of physical activity are risk factors for breast cancer. Polyphenols, flavonoids, and other phytochemicals in fruits and vegetables prevent or alleviate breast and other cancers (Guo et al., 2020). Similarly, an extract from an asparagus by-product containing phenolic compounds, especially rutin and glucosides, significantly reduced the viability of MCF-7 breast cancer cells when treated with 500 µg·mL-1 of the asparagus extract for 48 h (Romani et al., 2021). The anti-cancer activity of asparagus extract against MCF-7 breast cancer cells was explained by its pro-antioxidant effects against tumor cells, the inhibition of MCF-7 cell proliferation, and the reduction of MCF-7 cell migration (Romani et al., 2021). In addition, other studies have demonstrated that the hydroxycinnamic acid, flavonols, lignans, and saponin compounds present in asparagus spears contribute to the reduction of breast cancer risk (Jiménez-Sánchez et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2020; Romanos-Nanclares et al., 2020).

The rutin content was negatively correlated with the viability of HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells (p < 0.05; r = 0.999) and the viability of MCF-7 breast cancer cells (p < 0.05; r = 0.999) (Table 2), indicating that the high rutin content in the UC157 cultivar allows this cultivar to exhibit high anti-cancer activity against HCT-116 colorectal and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cao et al. (2022b) similarly reported that the viability of HCT-116 colorectal and MCF-7 breast cancer cells showed significant negative correlations with the polyphenol and rutin contents in Atlas cultivars. In addition, there was a negative correlation (p < 0.05; r = 0.999) between the viability of HCT-116 colorectal and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. However, the present result demonstrates that the viability of Calu-6 lung cancer cells was not significantly correlated with the rutin content in asparagus spears of the UC157 cultivar. It was reported that the viability of Calu-6 lung cancer cells is strongly negatively correlated with rutin content in Atlas cultivar (Cao et al., 2022b).

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the rutin content and bioactivity of UC157 asparagus spears

Anti-obesity effect

In this study, the anti-obesity effects of the asparagus spears of the four examined asparagus cultivars were evaluated by determining the cytotoxicity of the spear extract against 3T3-L1 cells and lipid accumulation. Obesity is a common metabolic disease that characterized by an excessive accumulation of fat in the human body (Lee et al., 2017). Obese people are prone to coronary heart disease and arthritis (Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2019). The consumption of vegetable containing fibers, vitamins, phenolics, and other bioactive compounds is thought to reduce obesity by inhibiting pancreatic lipase and phosphodiesterase activity, causing cytotoxicity against adipocyte, and inhibiting the differentiation of preadipocytes (Kim et al., 2010; Marrelli et al., 2020).

The viability of 3T3-L1 cells varied from 80.15–90.33% of the control when the cells were incubated with 50 µg·mL-1 of the extract (Table 3). The viability of the cells decreased to 69.30–78.69% of the control cells when the extract concentration was increased to 800 µg·mL-1. This finding indicates that the growth and proliferation of 3T3-L1 cells was inhibited by the extracts of the four asparagus cultivars at concentrations from 50–800 µg·mL-1. In addition, there was no significant difference in the effect on adipocyte viability among the four cultivars.

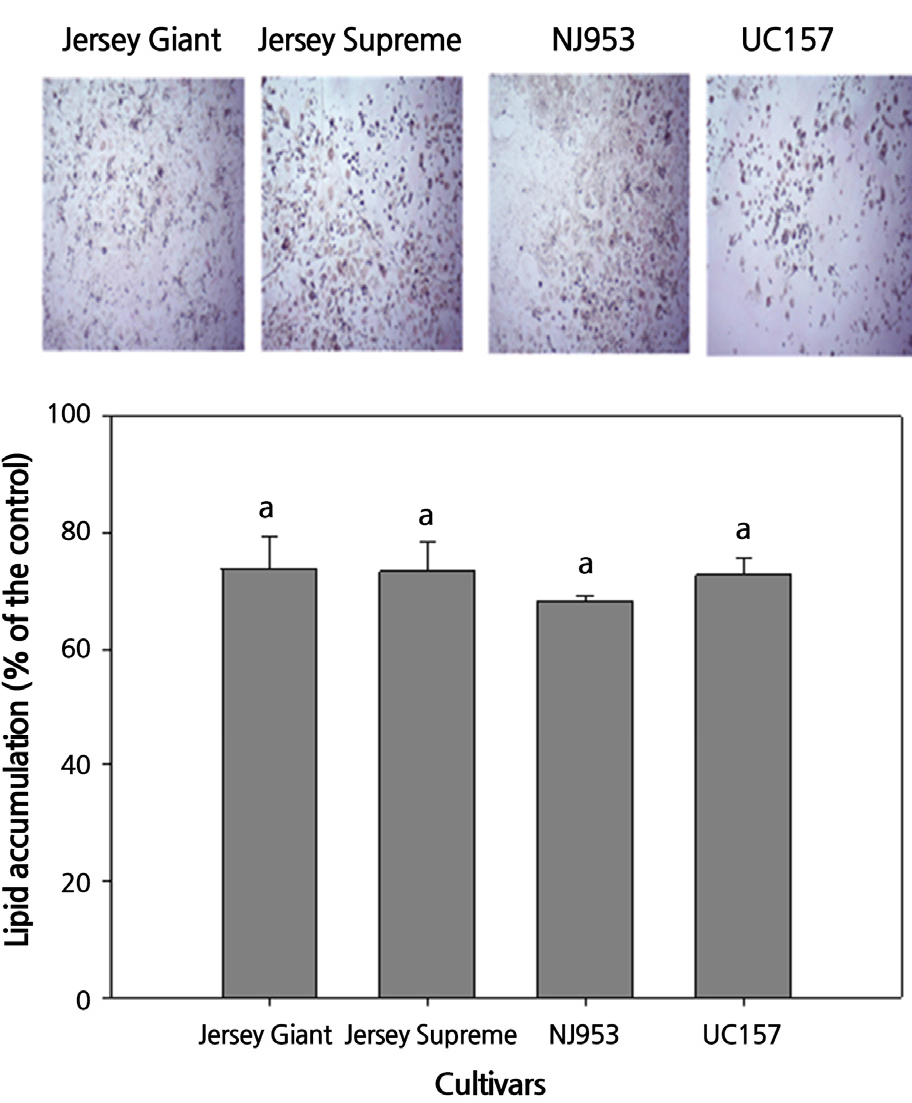

The effect of the asparagus spear extracts from the four cultivars on lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells was determined (Fig. 4). Cells incubated with the spear extracts exhibited a lipid droplet accumulation rates ranging from 68.30–73.76%, compared to the control sample. The decrease in lipid accumulation in the cells may be due to the decrease in cell viability after incubation with the asparagus extracts (Table 3). The decreased lipid accumulation indicates that the asparagus extract inhibits the differentiation of the preadipocytes to adipocytes. The effects on lipid accumulation among the four asparagus cultivars were not significantly different. This was consistent with the result of the viability of the 3T3-L1 cells (Table 3). The decreases in 3T3-L1 adipocyte viability and lipid droplet accumulation of the 3T3-L1 cells indicate that consumption of asparagus spears may prevent and reduce obesity. Phenolic compounds in asparagus and other vegetables have been demonstrated to show anti-obesity effects (Trigueros et al., 2013).

Fig. 4.

Lipid accumulation of the cells treated with spear extracts from the four asparagus cultivars (% of the non-treated sample). Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences based on Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Viability of 3T3-L1 cells treated with the spear extracts of four asparagus cultivars grown in the open field at 21-month-old plants

| Cultivar | Cell Viability, % of control | ||||

| Concentration (µg·mL-1) | |||||

| 50 | 100 | 200 | 400 | 800 | |

| Jersey Giant | 80.15zay | 79.85 a | 75.09 a | 72.83 a | 71.24 a |

| Jersey Supreme | 84.78 a | 76.27 a | 72.70 a | 67.34 a | 69.30 a |

| NJ953 | 90.09 a | 79.28 a | 77.11 a | 78.74 a | 77.83 a |

| UC157 | 90.33 a | 83.73 a | 75.80 a | 76.38 a | 78.69 a |

Conclusion

Asparagus spears of the four examined cultivars showed higher anti-cancer activity against HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells compared to that against Calu-6 lung and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. The UC157 cultivar contained the highest rutin content and effectively inhibited the proliferation of HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells. The rutin content in the spears of the four cultivars gradually decreased from the tip to the basal segments. The spear extracts of the four cultivars exhibited anti-obesity effect as well. These results suggest that the UC157 cultivar is a promising cultivar with its high rutin content and anti- cancer activity against HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells.