Introduction

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Cultivation Methods

Investigation of Growth Characteristics

Analysis of Ginsenosides

Results

Breeding History

Qualitative Traits

Growth Characteristics

Resistance to Physiological Disorders, Diseases, and Pests

Root Yield and Ginsenoside Content

Discussion

Introduction

Panax ginseng Mey. (ginseng) is a perennial plant belonging to the family Araliaceae in the order Umbellales, which grows or is cultivated in Korea, northeastern China (Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang provinces), and in the vicinity of Primorsky Krai in Russia (Woo et al., 2004). With increasing income levels and changes in consumption trends, particularly regarding health, the size of the health supplement market (KRW 2,522.1 billion, 2018) and the exports of health supplement products ($114.3 million, 2018) have increased annually. In particular, sales of red ginseng and ginseng in 2018 (KRW 1,130.1 billion) accounted for 44.8% of all market sales, and this proportion is continuously increasing (MFDS, 2019). The amount of ginseng produced in Korea (KRW 830.7 billion, 2018) accounts for 1.9% of domestic agricultural production. Ginseng exports ($188 million in 2018) account for 3.1% of domestic agricultural exports (MAFRA, 2019).

As a consequence of the ongoing increase in ginseng consumption and export, the cultivation of this plant has begun to expand beyond traditional suitable areas (fields and mountains), with cultivation in paddy fields (5,625 ha in 2018) accounting for 36.4% of the total cultivation area (15,452 ha). However, this expansion in cultivation has been accompanied by increases in physiological disorders, such as etiolation and rusty root disease. Nevertheless, the area of paddy fields under ginseng cultivation has gradually increased owing to the lack of more suitable cultivation sites (Lee et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013), thereby increasing the frequency of wet injuries.

As a consequence of the ongoing increase in ginseng consumption and export, the cultivation of this plant has begun to expand beyond traditional suitable areas (fields and mountains), with cultivation in paddy fields (5,625 ha in 2018) accounting for 36.4% of the total cultivation area (15,452 ha). However, this expansion in cultivation has been accompanied by increases in physiological disorders, such as etiolation and rusty root disease. Nevertheless, the area of paddy fields under ginseng cultivation has gradually increased owing to the lack of more suitable cultivation sites (Lee et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013), thereby increasing the frequency of wet injuries.

As a semi-heliophobic and cool season crop, ginseng is generally difficult to cultivate, as it requires a specific environment under shade. Moreover, it is difficult to distinguish genetic mutations because of large differences in growth characteristics, depending on environmental conditions (Kim et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2017). Furthermore, ginseng plants take at least 4 years to flower and fruit (4 years for one generation). Thus, seed production takes a long time, and the seed yields of 4-year-old plants are generally low, at only 40–60 seeds (Kwon et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2018). Accordingly, cultivar development by hybrid breeding, which requires a protracted breeding period, is yet to be performed. As an alternative, cultivars are being developed by pure-line selection, which commonly involves a relatively short breeding period (Seo et al., 2019).

Ginseng breeding has been conducted to obtain high yields, enhance functional properties, and ensure strong tolerance against physiological disorders and resistance to diseases. Starting with the two cultivars ‘Chunpoong’ and ‘Yunpoong’, which were developed in 2002, 32 cultivars have been developed in Korea to date (Kwon et al., 1998; Kwon et al., 2000; KSVS, 2019).

Recently, recurrence of atypical weather events, attributable to climate change, has been shown to have detrimental effects on ginseng cultivation. In particular, high temperatures and humidity, leading to increasing frequency of disease, threatens stable production (Jo et al., 2017). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop cultivars with high tolerance to environmental stress and resistance to diseases that can respond to climate change, thereby ensuring stable production of ginseng. In this study, we describe the breeding history and main characteristics of a new ginseng cultivar, ‘Cheonmyeong’, which is characterized by abundant roots and resistance to rusty root disease.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Cultivation Methods

The new cultivar ‘Cheonmyeong’ was collected as a genetic resource on July 3, 2008, from the farm race field, Buyeo, Chungnam, Korea (36°12'53.7''N 126°46'22.3''E), based on the discovery of a previously unreported qualitative trait; namely, an apricot-colored pericarp. A postmaturity assessment was performed for the collected seeds via stratification treatment from July 21 to November 10, 2008, in a greenhouse (Eumseong, Chungbuk, Korea) at the Department of Herbal Crop Research, National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science (NIHHS). Thereafter, the dehisced seeds were sown in a nursery at the NIHHS on November 15, 2008. The ginseng seedlings were cultivated for more than 1 year, until March 2010, and were then transplanted to the main breeding fields at a planting density of 7 rows × 10 columns/90 × 180 cm.

Shading nets, which comprised three layers of blue and one layer of black nets, were installed before emergence. In June, two black layers were added over the nets to prevent heat injury. The cultivation process complied with Ginseng Good Agricultural Practices, including the pre-planting treatment and pest management (RDA, 2012a).

Production performance of the new cultivar was assessed by the NIHHS (Eumseong, Chungbuk, Korea) for 2 years (2012 and 2013). This was followed by 2 years (2014 and 2015) of regional adaptation evaluation, conducted in the three regions of Eumseong, Youngju, and Cheorwon, with ‘Chunpoong’ used as a control cultivar for comparative purposes.

Investigation of Growth Characteristics

We investigated leaf color, leaf color at senescence, stem and petiole color, fruit color, and cross-sectional leaflet shape as unique traits of the cultivar, whereas sprouting period, flowering period, fruit-ripening period, stem length, stem diameter, root length, root diameter, and root weight were examined as growth characteristics in accordance with the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) inspection standards (UPOV, 2004).

Physiological disorders, diseases, and invertebrate pests were investigated by visual inspection of the aboveground and belowground sections of 100 individuals, according to the inspection standards prescribed by the Rural Development Administration (RDA, 2012b). Physiological disorders affecting aboveground parts were categorized into etiolation, brown spot, atrophy, and heat injury, whereas those affecting belowground parts were categorized into rusty roots and roots with rough skin, all of which were divided into six grades. Grade 0 indicated absence of the disorder, and grades 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 indicated disorders below 1%, 1–10%, 10–25%, 25–40%, and over 40%, respectively. Diseases, such as damping-off, Alternaria blight, anthracnose, Phytophthora blight, root rot, and invertebrate pests, such as mulberry mealybugs and nematodes, were inspected in the fields. Disease symptoms and damage resulting from invertebrate pests were divided into six grades. Grade 0 indicated the absence of disease or invertebrate pests, and grades 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 indicated disease below 1%, 1–5%, 5–10%, 10–20%, and over 20%, respectively.

Analysis of Ginsenosides

For a comparative analysis of ginsenosides in ginseng, the roots of 4-year-old plants of the new cultivar ‘Cheonmyeong’ and the control cultivar ‘Chunpoong’ were harvested, washed with clean water, dried using a freeze dryer (PVTFD30R; Il-Shin Lab, Seoul, Korea), and then ground using a grinder (SMX 800SP; Shinil, Seoul, Korea).

The ginsenoside content was analyzed using a 1200 series high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) equipped with a C18 column (Kinetex XB, 100 mm × 4.6 mm, particle size 2.6 µm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The column temperature was set to 40°C, the flow rate was 1.0 mL·min-1, and the detection wavelength was 203 nm. The samples were injected in increments of 10.0 µL using an auto-injector, and ultra-pure water (+0.0005% formic acid) and 100% acetonitrile were used as mobile phase solvents A and B, respectively. Solvent B was maintained at 18% from 0 to 18 min, and then increased to 28% from 18 to 23 min, 31% from 23 to 30 min, 33% from 30 to 45 min, 39% from 45 to 5 min, 41% from 52 to 65 min, 45% from 65 to 75 min, and 90% from 75 to 85 min. After maintaining solvent B at 90% from 85 to 95 min, it was reduced to 18% from 100 to 105 min and maintained at this level. Each ginsenoside was quantified by comparing the HPLC peak areas of ginsenoside in the analyzed samples with those of the respective external standards. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three sample replicates.

Results

Breeding History

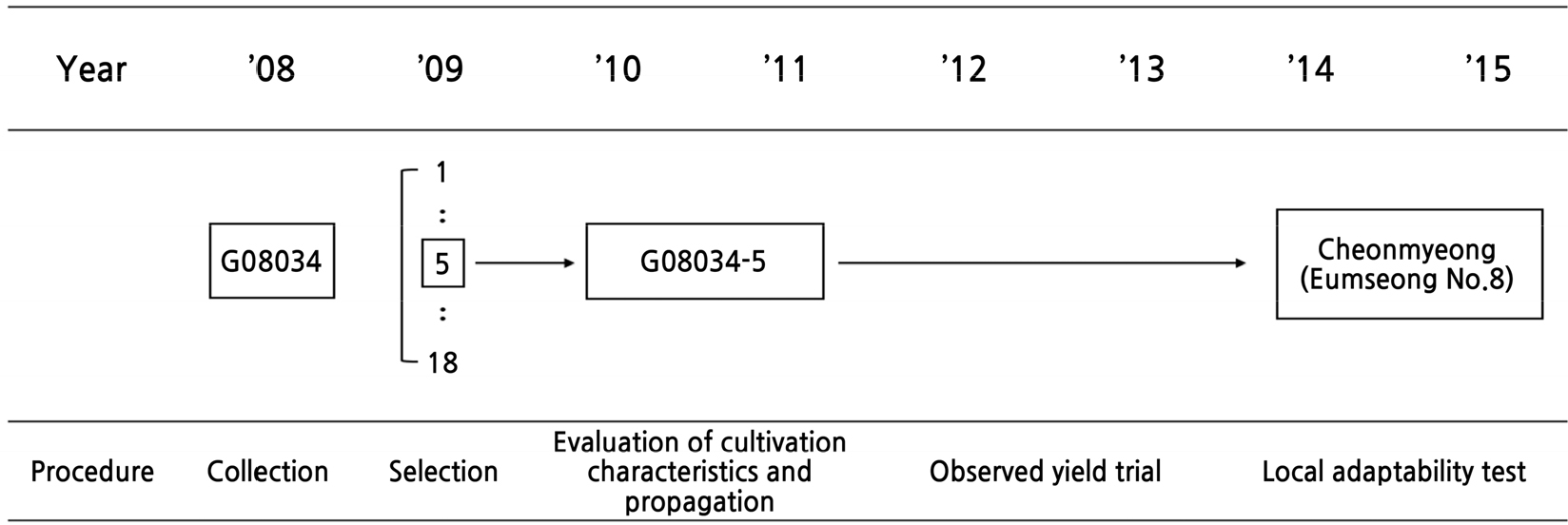

In 2008, seeds of the new cultivar ‘Cheonmyeong’ were collected from the farm race field, Buyeo, Chungnam, Korea, to develop an environmental stress-tolerant cultivar. After seeding, in 2009, one plant was selected from 10 individuals, its characteristics were assessed, and multiplication was conducted from 2010 to 2011. The new cultivar was assigned the breeding line name ‘Eumseong No. 8’ for determining the observed yield trial using the G08034-5 line, which was conducted between 2012 and 2013, and the local adaptability evaluation was conducted for 2 years from 2014 to 2015 (Fig. 1). Characterized by high yield and strong resistance against rusty root disease, ‘Eumseong No. 8’ was registered as a new breed by the Korea Seed and Varieties Service in 2019 under the name ‘Cheonmyeong’ (grant number 7467), and has been accorded plant breeders’ rights.

Fig. 1.

Pedigree diagram of the new ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivar, ‘Cheonmyeong’. The Korean ginseng selection, breeding, and development project began in 2008, with a focus on collecting the phenotypic variance of the aerial part, Panax ginseng Meyer. Evaluations of the cultivation and propagation characteristics were conducted in 2010–2011, and then a yield test (observed yield trials) was conducted for 2 years (2012–2013). ‘Eumseong No. 8’ performed consistently well for 2 years (2014–2015) at the three locations in the local adaptability test in Korea, and it was released as ‘Cheonmyeong’.

Qualitative Traits

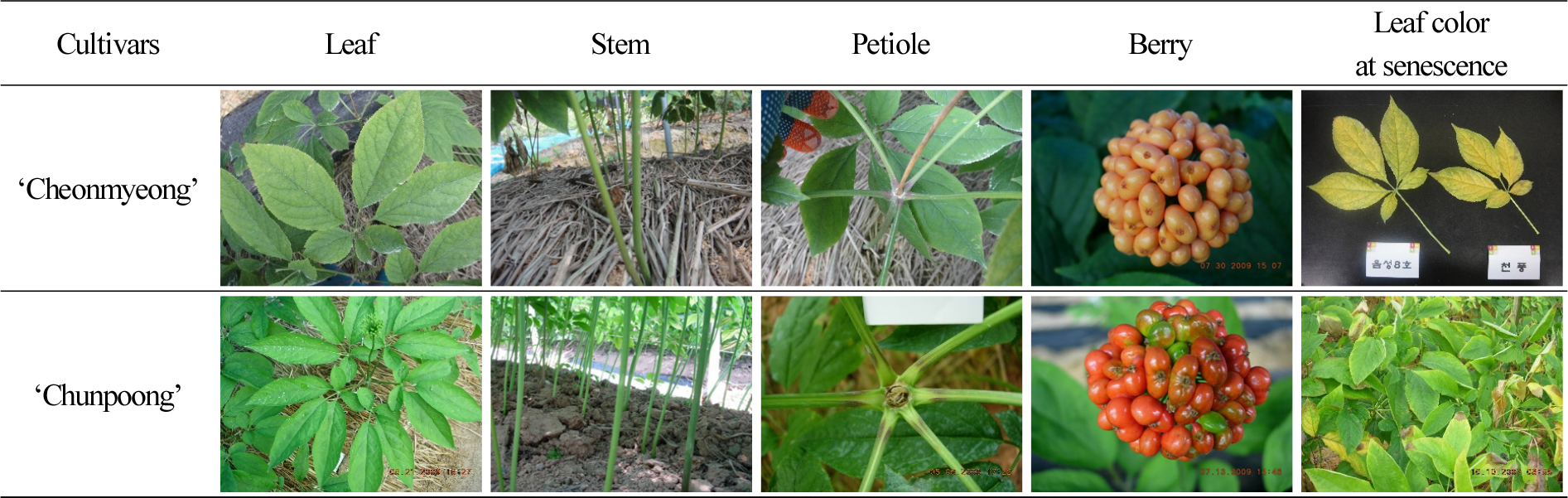

To assess qualitative traits and growth characteristics, 4-year-old ‘Cheonmyeong’ plants were compared with their ‘Chunpoong’ counterparts. The new cultivar had green leaves and a yellow leaf color during senescence. Its leaflet shape in cross-section was flat, which contrasted with the concave type of ‘Chunpoong’. The entire stem was green, and the petiole and basal portion of the leaf were colored light purple. Leaf color during the senescence of ‘Cheonmyeong’ was similar to that of ‘Chunpoong’. ‘Cheonmyeong’ had a characteristic yellowish orange pericarp, which clearly distinguished it from the control cultivar, with its reddish-pink pericarp. This qualitative trait is a unique feature of the new cultivar, which has never been observed in existing cultivars (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Qualitative characteristics of the aboveground parts of the new ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivar ‘Cheonmyeong’ and the control cultivar ‘Chunpoong’

| Cultivar | Color | LSCSy | |||

| Leaf | LCSz | Stem | Berry | ||

| Cheonmyeong | Green | Yellow | Pale purple | Yellowish orange | Flat |

| Chunpoong | Green | Yellow | Pale purple | Reddish pink | Concave |

Fig. 2.

Qualitative characteristics of the aboveground parts of ‘Cheonmyeong’ and ‘Chunpoong’ ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivars. Qualitative traits examined were leaf shape, distribution of anthocyanin coloration of the stem, presence or absence of pigment in the petiole, fruit color, and pigmentation of autumn leaf. ‘Cheonmyeong’ had broad elliptical leaves with plain leaflets, whereas ‘Chunpoong’ had narrow elliptical leaves and concave leaflets. Anthocyanin coloration on the stem in two cultivars (‘Chunpoong’ and ‘Cheonmyeong’) was present in the lower section. ‘Cheonmyeong’ had a characteristic yellowish orange pericarp, whereas ‘Chunpoong’ had a reddish pink pericarp. Leaf color during senescence in ‘Cheonmyeong’ was similar to that in ‘Chunpoong’.

Growth Characteristics

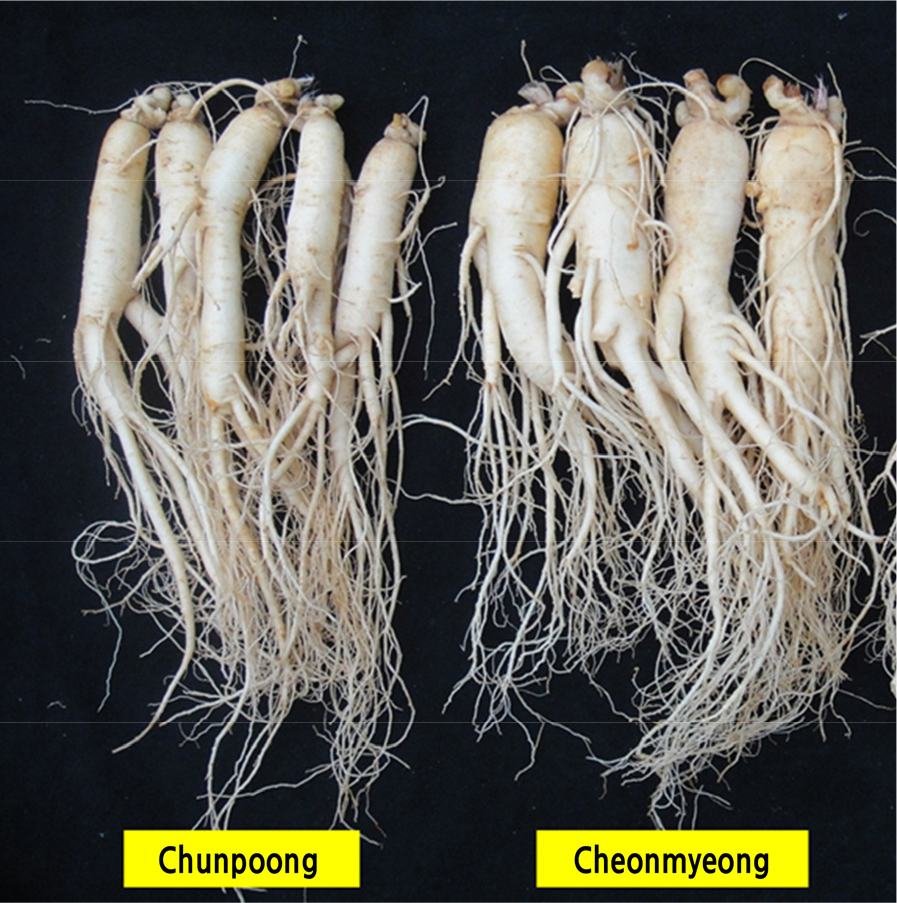

Sprouting (April 18) and flowering (May 16) dates of ‘Cheonmyeong’ were approximately 2 days earlier than those of ‘Chunpoong’ (April 20 and May 18 for sprouting and flowering, respectively). Similarly, the fruit-ripening date of the new cultivar (July 20) was 3 days earlier than that of the control cultivar (July 23) (Table 2). The mean length of the stems of ‘Cheonmyeong’ was 33.5 ± 2.8 cm, which was approximately 3.3 cm shorter than that of ‘Chunpoong’ (36.8 ± 1.9 cm). Stem diameter of ‘Cheonmyeong’ was 6.5 ± 2.0 mm, which was approximately 0.3 mm thinner than that of ‘Chunpoong’ (6.8 ± 1.4 mm). The length and width of the leaves of ‘Cheonmyeong’ were 13.6 ± 1.3 cm and 6.1 ± 1.1 cm, respectively, and were approximately 0.3 cm longer/wider than those of ‘Chunpoong’ (13.3 ± 1.7 cm and 5.8 ± 1.0 cm for length and width, respectively). The root length ‘Cheonmyeong’ (28.9 ± 0.8 cm) was similar to that of the control cultivar (28.7 ± 0.8 cm), whereas the length of the main root (8.6 ± 0.2 cm) was approximately 0.9 cm shorter than that of ‘Chunpoong’ (9.5 ± 0.8 cm). The diameter of the main root and the weight of fresh roots were 26.8 ± 3.1 mm and 40.1 ± 5.7 g, respectively, which were approximately 8.6 mm thicker and 8.7 g heavier than those of ‘Chunpoong’ (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Emergence, flowering, and berry maturation periods of the new ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivar ‘Cheonmyeong’ and the control cultivar ‘Chunpoong’

| Cultivar | Sprouting date | Flowering date | Fruit-ripening date |

| Cheonmyeong | April 18 | May 16 | July 20 |

| Chunpoong | April 20 | May 18 | July 23 |

Table 3.

Mean (± standard deviation) growth characteristics of the aboveground and belowground parts of the new ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivar ‘Cheonmyeong’ and the control cultivar ‘Chunpoong’

| Cultivar |

Stem length (cm) |

Stem diameter (mm) |

No. of stems (n) |

Petiole length (cm) |

Leaf length (cm) |

Leaf width (cm) |

No. of leaves (n) |

Root length (cm) |

Main root length (cm) |

Main root diameter (mm) |

Weight of fresh root (g·plant-1) |

| Cheonmyeong | 33.5 ± 2.8 bz | 6.5 ± 2.0 a | 1.5 ± 0.5 a | 9.8 ± 1.4 a | 13.6 ± 1.3 a | 6.1 ± 1.1 a | 26.1 ± 3.7 a | 28.9 ± 0.8 a | 9.6 ± 0.2 a | 26.8 ± 3.1 a | 40.1 ± 5.7 a |

| Chunpoong | 36.8 ± 1.9 a | 6.3 ± 1.4 a | 1.0 ± 0.0 b | 8.7 ± 0.9 b | 13.3 ± 1.7 a | 5.8 ± 1.0 b | 23.2 ± 2.2 b | 28.7 ± 0.8 a | 9.5 ± 0.8 a | 18.2 ± 1.4 b | 31.4 ± 3.3 b |

Fig. 3.

Qualitative characteristics of the belowground parts of ‘Cheonmyeong’ and ‘Chunpoong’ ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivars. Qualitative traits were the color of the main root, the presence or absence of stolons, and the shape of the main root. The roots of ‘Cheonmyeong’ were cream in color, whereas those of ‘Chunpoong’ were bright cream. The two cultivars possessed stolons near the rhizome. The main roots of ‘Cheonmyeong’ were thicker and heavier than those of ‘Chunpoong’.

Resistance to Physiological Disorders, Diseases, and Pests

The occurrence of major ginseng diseases, pests, and physiological disorders in ‘Cheonmyeong’ were compared with those of ‘Chunpoong’. Aboveground physiological disorders, such as etiolation, brown spot, and atrophy, were rarely observed in ‘Cheonmyeong’. The new cultivar also showed minimal symptoms associated with belowground physiological disorders, such as rough skin. Compared with ‘Chunpoong’, the new cultivar showed moderate tolerance to high temperature and a stronger resistance to belowground rusty root, which has a considerable detrimental effect on the quality of ginseng (Table 4). The extent of damage to ‘Cheonmyeong’ caused by high temperature was graded as 3 (occurrence rate: 1–10%), and damage by rusty root as grade 1 (occurrence rate: < 1%), while high temperature damage to ‘Chunpoong’ was grade 5 (occurrence rate: 10–25%) and rusty root damage was grade 3 (occurrence rate: 1–10%). ‘Cheonmyeong’ was also found to be tolerant to damping-off and root rot, and showed moderate resistance to Alternaria blight and anthracnose. We failed to detect any occurrence of Phytophthora blight in the new cultivar, and found that it had resistance to pests such as mulberry mealybugs and nematodes (Table 5).

Table 4.

Responses of ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivars to physiological injuries from diseases and invertebrate pests

| Cultivar | Aboveground | Belowground | |||||

|

Etiolation (0–9)z |

Brown spot (0–9)z |

Atrophy (0–9)z |

Heat injury (0–9)z |

Rusty (0–9)z |

Rough skin (0–9)z | ||

| Cheonmyeong | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| Chunpoong | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 1 | |

Table 5.

Incidence of diseases and invertebrate pests in ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivars

| Cultivar | Disease | Invertebrate pest | ||||||

|

Damping-off (0–9)z |

Alternaria blight (0–9)z |

Anthracnose (0–9)z |

Phytophthora blight (0–9)z |

Root rot (0–9)z |

Mulberry mealybug (0–9)z |

Nematode (0–9)z | ||

| Cheonmyeong | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Chunpoong | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

Root Yield and Ginsenoside Content

Our local adaptability evaluation of the root yields of 4-year-old ‘Cheonmyeong’ (from 2014 to 2015) revealed that the average yield was 571.8 ± 99.7 kg·10 a-1; this was approximately 28% higher than that obtained for ‘Chunpoong’ (444.1 ± 110.4 kg·10 a-1) (Table 6). The total content of ginsenosides, which are regarded as representative functional substances of ginseng, was higher in ‘Cheonmyeong’ (31.70 ± 1.83 mg·g-1) than in ‘Chunpoong’ (26.62 ± 1.60 mg·g-1). Regarding the 12 individual ginsenosides, we failed to detect Rg2 (20s) in ‘Cheonmyeong’, whereas Rh1 and Rg5 were not detected in the control cultivar ‘Chunpoong’. In ‘Cheonmyeong’, the concentrations of Rg1 (which improves memory and learning), Rf (which is effective for neuronal oscillation), and Rc (which has anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects) were 7.56 ± 0.45, 2.85 ± 0.15, and 3.70 ± 0.25 mg·g-1, respectively, and were relatively higher than concentrations of the same ginsenosides measured in ‘Chunpoong’ (Table 7).

Table 6.

Summarized results of the local adaptability test for ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivars in 2014 and 2015

| Region | Average root yield ± standard deviation (kg·10a-1) |

Index (A/B) | ||||||

| Cheonmyeong | Chunpoong | |||||||

| 2014 | 2015 | Average (A) | 2014 | 2015 | Average (B) | |||

| Eumseong | 484.0 ± 7.0 | 721.7 ± 2.1 | 602.8 ± 130.3 az | 327.7 ± 12.6 | 564.7 ± 8.0 | 446.2 ± 130.2 b | 135.1 | |

| Punggi | 464.0 ± 2.0 | 595.7 ± 3.5 | 529.8 ± 72.2 a | 325.7 ± 6.8 | 464.7 ± 3.2 | 395.2 ± 76.3 b | 134.1 | |

| Cheorwon | 500.3 ± 2.1 | 665.3 ± 4.7 | 582.8 ± 90.4 a | 386.3 ± 7.4 | 595.7 ± 3.5 | 491.0 ± 114.8 b | 118.7 | |

| Average | 482.8 ± 16.2 | 660.9 ± 54.8 | 571.8 ± 99.7 a | 346.6 ± 30.9 | 541.7 ± 59.5 | 444.1 ± 110.4 b | 128.8 | |

Table 7.

Concentrations of individual and total ginsenosides (average ± standard deviation) in root samples of two ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivars, ‘Cheonmyeong’ and ‘Chunpoong’

Discussion

With the recent expansion in ginseng cultivation across Korea, there has been a tendency for excessive use of poultry, cattle, swine manure, and organic matter on farms, regardless of the existing soil fertility. This has consequently increased the occurrence of rusty root, a disease characterized by the development of yellowish brown or reddish-brown round or irregular spots on the root epidermis, which subsequently spreads to the entire root (Eo et al., 2018). If this occurs in 1- or 2-year-old plants, it can inhibit root thickening, whereas in plants older than 4 years, the root epidermis becomes rougher or, in severe cases, develops cracks (Hong et al., 2019). Accordingly, there has been an increased demand for the development of new ginseng cultivars that are more resistant to rusty root disease.

In the past, soil fertility and cultivation practices were the main factors determining the yield and quality of ginseng. However, with the development and optimization of cultivation practices, the yield and quality of ginseng are now determined primarily by genetic factors. Nevertheless, the development of new cultivars has been slower than anticipated. This has led to farmers cultivating local landraces that are typically characterized by low yields and high vulnerability to diseases, pests, and physiological disorders, thereby hampering the stable production of ginseng (Hong et al., 2018). On the basis of production performance tests and local adaptability evaluations (Eumseong, Youngju, and Cheorwon), we found that the newly developed ‘Cheonmyeong’ had a higher root biomass, stronger resistance to diseases (particularly rusty root) and pests, and better tolerance of physiological disorders compared with ‘Chunpoong’ (a verified rusty root-tolerant cultivar). Results reveal that ‘Cheonmyeong’ is relatively resistant to the major diseases of ginseng compared with ‘Chunpoong’. Additionally, we found that, compared with ‘Chunpoong’, ‘Cheonmyeong’ contained higher amounts of ginsenosides, the main functional substances of ginseng, particularly Rg1, Rf, and Rc. Accordingly, it is anticipated that cultivation of the new ginseng cultivar ‘Cheonmyeong’ will enable the stable production of ginseng and thereby contribute to increasing farm incomes.

Farmers cultivating ‘Cheonmyeong’ should, however, be aware that although this cultivar showed a strong resistance to rusty root disease, the occurrence of rough skin remains high when plants are cultivated on farms or in paddy fields with a high moisture content. Therefore, it must be ensured that the land used for planting is sufficiently drained. Furthermore, the development of multi-stem forms is a relatively frequent phenomenon, given that excessive growth of aboveground parts can occur when plants are cultivated in a field with a high fertilizer content. Accordingly, it is recommended to apply less fertilizer to ensure the production of plants with desirable growth characteristics.