Introduction

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Aeration and Temperature Treatments

Seedling Growth Parameters

Photosynthetic and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

Mineral Content

Statistical Analysis

Results

Growth Characteristics

Photosynthetic and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

Mineral Content

Discussion

Introduction

Given the increased interest in food safety and health, the demand for natural health products from medicinal plants is growing rapidly worldwide. Medicinal plants contain various secondary metabolites and are valuable resources for the food and medical supply industries (Kozai and Niu, 2019). However, it is difficult to produce high-quality and stable plant-derived materials in the field owing to climate change, global warming, and soil pollution. Plant factories with artificial lighting (PFALs) are plant production systems that can produce plants on a large scale throughout the year by controlling shoot and root zone environmental conditions. PFALs are suitable for the stable production of high-value plants because more precise environmental control is possible in PFALs than in greenhouses or fields (Kozai, 2018).

The medicinal plant coastal glehnia (Glehnia littolaris F. Schmidt ex. Miq.) is an Apiaceae perennial herb that is mainly distributed in coastal areas (Kim, 2013). Traditionally, its shoots and roots have been used for pharmaceutical purposes, as they contain various health-promoting phytochemicals (Hiraoka et al., 2002). Extracts of coastal glehnia are known to have high levels of antioxidant, antitumor, and anti-rheumatic compounds (Hiraoka et al., 2002; Um et al., 2010). For the stable mass production of medicinal plants, stable growing conditions must be established for the entire production process, from seed germination to harvest. In a previous study, dormancy breaking and using the proper germination temperature of coastal glehnia seeds were found to shorten the germination time and increase the germination rate (Yeom et al., 2021). The main problem on farms cultivating coastal glehnia is the delay in harvesting and the decrease in productivity due to slow seedling growth rate. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the environmental conditions required for seedling growth and development.

Among various environmental factors, the plant temperature, affected by the air and root-zone temperature, is related to enzyme activity in physiological responses, the regulation of photosynthesis, the plant phenology, and growth performance. Accordingly, this factor affects plant metabolic activity, yield, and quality levels (Tuteja and Gill, 2013; Jeon et al., 2022). Plant responses to the air temperature are driven by the minimum, optimum, and maximum cardinal temperatures. The plant growth rate increases linearly with the minimum cardinal-to-optimal temperatures and decreases with the optimum- to-maximum cardinal temperatures, and long-term exposure to excessively low or high temperatures leads to suppressed growth and reduced metabolic activity in plants due to stress (Kozai and Niu, 2019). Low temperatures affect the respiratory process, material movements and inhibit enzyme activity in the cell membrane structure (Criddle et al., 1997). High temperatures of up to 30°C promote plant respiration, whereas higher temperatures of 32–35°C induce a decrease in the respiratory rate due to the denaturation of protoplasmic proteins and inhibit photosynthesis by deactivating photosynthetic enzymes, including Rubisco (Went, 1953; Criddle et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2022). Few studies have concentrated on root-zone responses to different temperatures. Some studies have reported changes in the absorption and transportation of water and minerals, root development, and the root architecture depending on the rhizosphere temperature (Aroca et al., 2002; Koevoets et al., 2016; Inkham et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2022). Because root development is systemically related to shoot growth and development (Leskovar and Stoffella, 1995), proper temperature management of the root zone is important during the cultivation process (Grossnickle, 2005). Moreover, root development at the seedling stage determines vigor and rooting and leads to faster cell division than shoot development; therefore, precise temperature control in the root zone can promote uniform growth (Went, 1953). Thus, this study aimed to determine the suitable temperature conditions for the shoot and root zones at the seedling stage to promote seedling growth in coastal glehnia.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The dormancy of coastal glehnia seeds was broken after ten weeks of cold stratification, as recommended by Yeom et al. (2021). The seeds were then sown in seed pouches (CYG seed germination pouch, Mega International, Roseville, MN, USA) and grown in a growth chamber (DS-51GLP; Dasol Scientific, Hwaseong, South Korea) at 20°C, 80% relative humidity, and 50 µmol·m-2·s-1 photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), radiated by white LED light for two weeks. The seedlings were transplanted to a deep-flow-technique (DFT) hydroponic system (32.5 × 22 × 23 cm, L × W × H) and cultivated in a PFAL module (4 × 2 × 3 m, L × W × H) for four weeks. The seedlings were rotated three times a week to ensure uniform light distribution on the leaves. The light conditions of the PFAL module were as follows: 300 µmol·m-2·s-1 of PPFD using a LED light source (red:white:blue, 8:1:1) for a 12 h photoperiod. We used the Hoagland/Arnon hydroponic nutrient solution (Hoagland and Arnon, 1950), with electrical conductivity of 1.0 dS·m-1 and pH of 5.8 ± 0.2. All treatments were performed immediately after transplanting.

Aeration and Temperature Treatments

In study I, the PFAL module was maintained at an air temperature (AT) of 20°C, and the aeration treatment also involved supplying oxygen to the hydroponic system using a bubble generator (DY104-A, Angelaqua, Guangdong, China) connected to an air supply device (HP-40, Hiblow, Osaka, Japan). No additional oxygen was supplied in the non-aeration treatment. Three root-zone temperatures (RZTs) were used: 15°C, 20°C, and 25°C. For the 15°C treatment, a cooling coil with a coolant flow was placed inside the DFT hydroponic system for the RZT, and a heater (AH-55, Amazon, Zhongshan, China) was installed in the system for the 25°C treatment. The 20°C treatment did not require additional devices. The RZT was continuously monitored in real time using analog and digital thermometers (OKE-6710CF, Sewon Oke, Busan, South Korea).

In study II, for different AT treatments, coastal glehnia seedlings were grown in two PFAL modules at 20°C and 25°C. For the 20°C AT module, the 25°C RZT was maintained using a heater (AH-55, Amazon, Zhongshan, China), whereas the 20°C RZT was maintained without additional devices. For the 25°C AT module, the 20°C RZT was maintained by installing a cooling coil, the 25°C RZT was maintained without additional devices. A bubble generator was installed inside the system to aerate the nutrient solution.

Seedling Growth Parameters

The fresh and dry weights of the shoot and root, the number of leaves, the crown diameter, and the shoot area were measured four weeks after the seedlings were transplanted in both studies I and II. The fresh weights of the shoots and roots were measured using an electronic scale (SI-234, Denver Instruments, Denver, CO, USA), after which the seedlings were dried in a freeze-drier (Alpha 2-4 LSCplus, Christ, Osterode, Germany) for 72 h to measure the dry weight. The crown diameter where the buds were generated was measured using a digital vernier caliper (BD500-300, Bluetec, Yongin, South Korea). The shoot area, including the area of the leaves and petioles, was measured using an area meter (LI-3100C, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Photosynthetic and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

The stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rate of the seedlings were measured using a portable photosynthetic system (LI-6800, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA) with a 1 × 3 cm leaf sectional chamber (LI-6800-12A, 1 × 3 SS, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA). The conditions for the leaf chamber were a relative humidity rate of 60%, reference CO2 level of 500 µmol·mol-1, and airflow of 700 µmol·s-1. The block temperature was identical to the AT. The LED light source in the leaf chamber had a light intensity level of 300 µmol·m-2·s-1, with 60% red light and 40% blue light.

The leaves were dark-adapted for 30 min to measure the maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm), relative electron transport rate (rETR), steady-state non-photochemical quenching in light (NPQ), and an effective photosystem Ⅱ quantum yield (QY) using a portable chlorophyll fluorometer (PAM-2000, Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Bayern, Germany). The rETR was calculated using the following equation: rETR = quantum yield of PSⅡ × PAR × 0.5 × 0.84 (ETR factor). Four seedlings per treatment were measured days before harvest.

Mineral Content

To analyze the mineral content of the seedlings, the dried seedlings were placed in a Teflon beaker and 70% nitric acid was added for 12 h. The sample solutions were heated to 125°C and reacted for 90 min using a heating block (Ecopre 3, OD-98-003, Odlab, Seoul, South Korea). The heated sample solutions were cooled and then catalyzed with 34% hydrogen peroxide, boiled at 200°C, and cooled for 1 d. To resuspend the minerals in the solution, 2% nitric acid was added to the cooled sample solutions, and distilled water was massed up to 70 g. All solutions were filtered using a quantitative filter paper. The minerals (P, K, S, Mg, Ca, and Fe) were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Optimia 7300 DV, Perkin Elmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Seven and ten seedlings per treatment were used to evaluate the seedling growth characteristics in studies I and II, respectively. Four seedlings with fully expanded leaves were used to measure the photosynthetic and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. Six dried shoots were used for the mineral analysis. One-way and two-way ANOVA were conducted for both studies, and the means of the treatments were compared using Tukey’s range test with SAS software (Statistical Analysis System, 9.4 Version, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Growth Characteristics

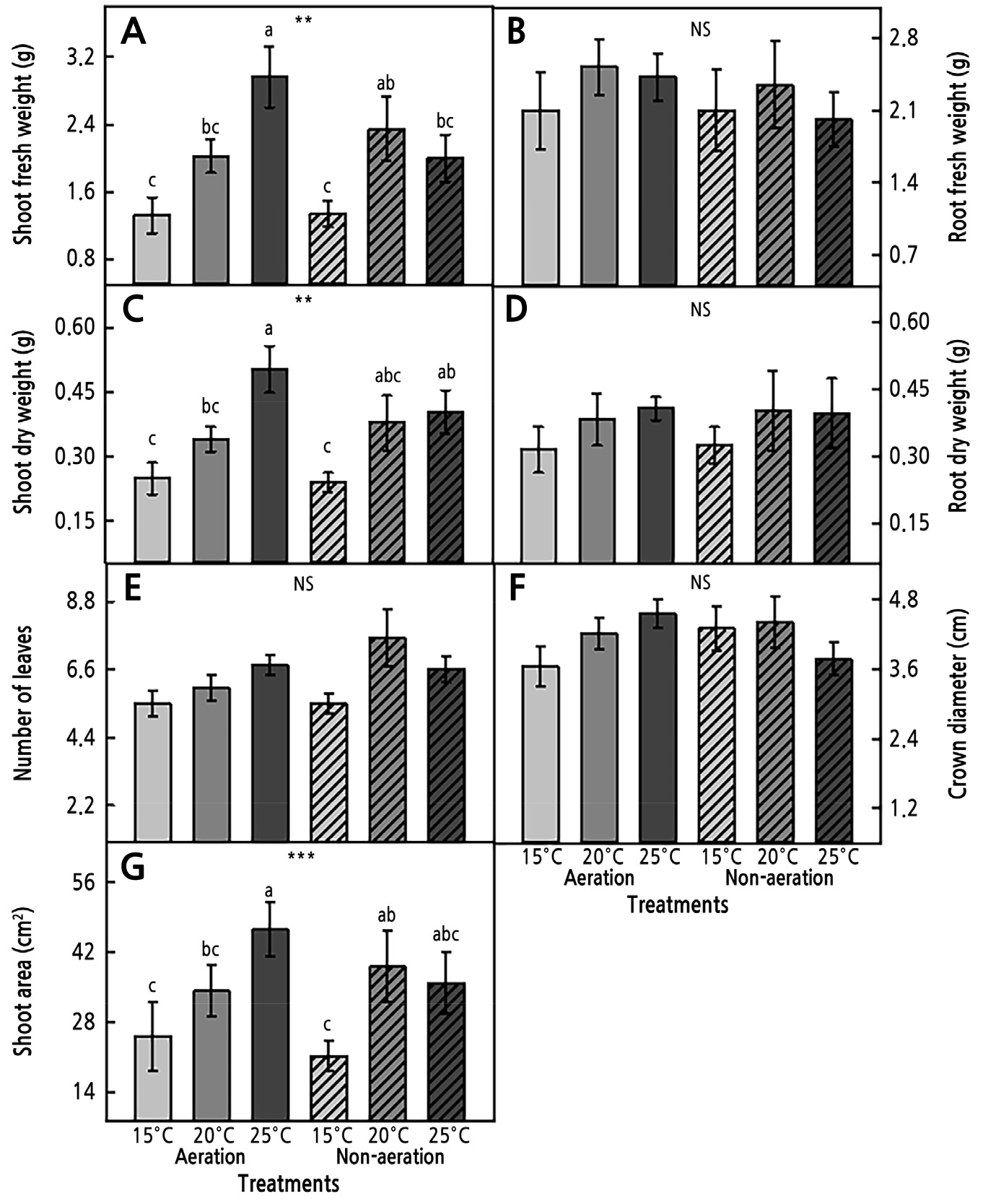

In study I, aeration and RZT were used to accelerate the growth of the coastal glehnia seedlings, with the growth characteristics examined four weeks after transplanting (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Aeration and non-aeration treatments did not significantly affect seedling growth, but different RZT treatments significantly affected the shoot fresh and dry weights and the shoot area (Table 1). As the temperature was increased, shoot growth gradually increased with aeration. The seedlings with a RZT of 25°C showed the highest shoot fresh and dry weights and shoot area compared to those with RZTs of 20°C and 15°C. Specifically, the shoot fresh weight of the seedlings treated with RZT of 25°C was 1.5 and 2.2 times higher than the weights of the seedlings treated with RZTs of 20°C and 15°C, respectively. There were no significant differences in the root fresh and dry weights, the number of leaves, or the crown diameter between the seedlings under the RZT and aeration treatments.

Fig. 1.

Fresh and dry weights of shoots (A and C) and roots (B and D), number of leaves (E), crown diameter (F), and shoot area (G) grown under aeration, non-aeration, and RZT treatments for four weeks after transplanting, where ** and *** indicate significance, respectively, at p < 0.01 and 0.001. NS denotes no significant difference (n = 7).

Table 1.

Two-way ANOVA results of fresh weight (FW) and dry weight (DW) of shoot and root, number of leaves (No. of leaves), shoot area, and crown diameter of coastal glehnia treated with root-zone temperature (RZT) and aeration for four weeks after transplanting

| Shoot FW | Shoot DW | Root FW | Root DW | No. of leaves | Shoot area | Crown diameter | |

| Aeration (A) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| RZT (B) | *** | *** | NS | NS | NS | *** | NS |

| A × B | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

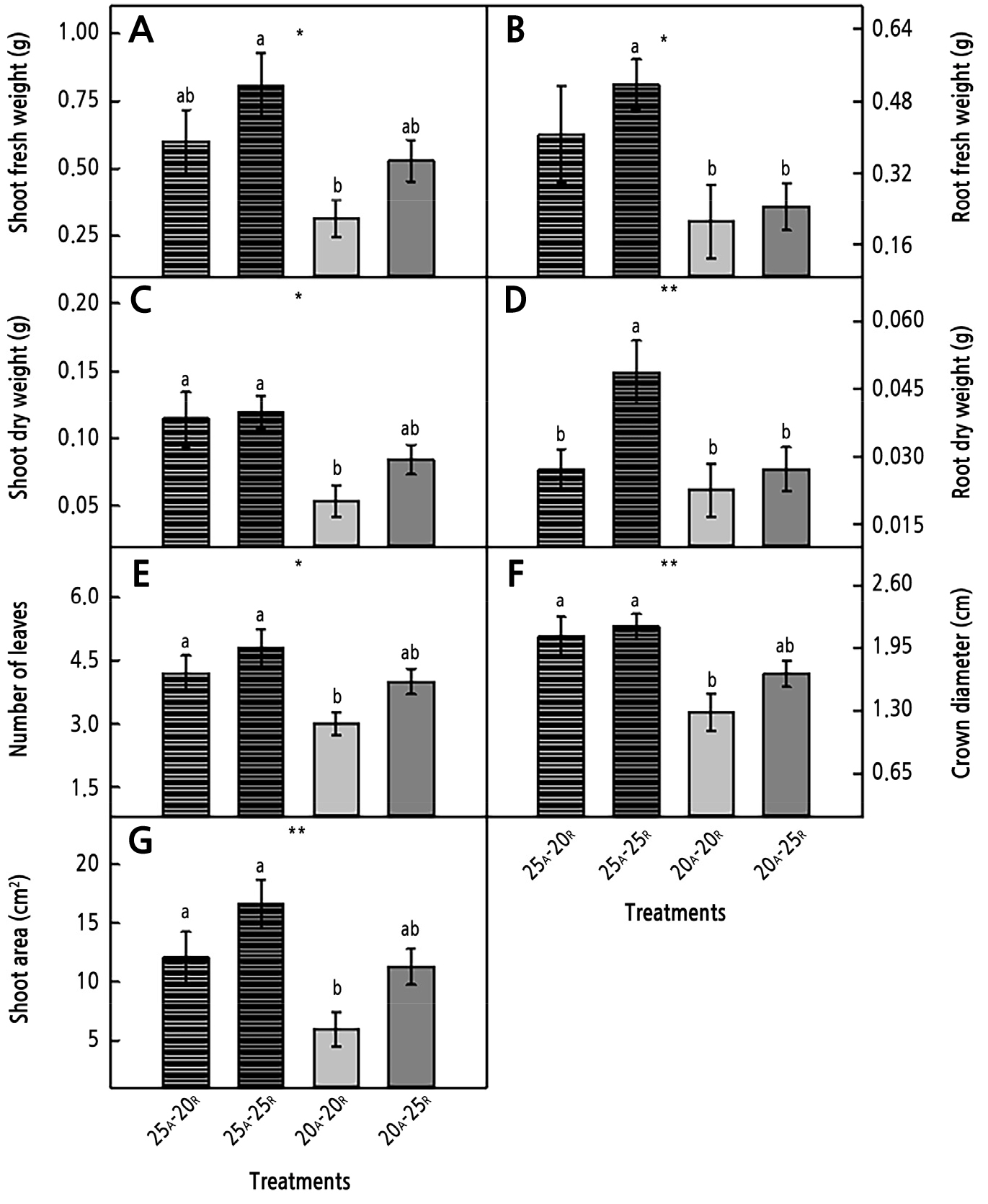

In study II, the seedlings treated with AT and RZT showed some growth differences (Fig. 2 and Table 2). All measured growth parameters showed a similar pattern. The AT 25°C treatment enhanced shoot growth (fresh and dry weights, number of leaves, and shoot area), root growth (fresh and dry weights), and the crown diameter compared to the AT 20°C treatment (Table 2). The RZT 25°C treatment led to significantly higher values of the shoot fresh weight, number of leaves, and shoot area relative to those of the RZT 20°C treatment. The seedlings under the treatment of AT 25°C with RZT 25°C showed the highest growth characteristics, and in particular, all growth parameters were significantly improved compared to the seedlings grown under AT of 20°C with a RZT of 20°C. The AT 25°C treatment with a RZT of 25°C led to 2.6, 2.4, 2.2, and 2.2 times higher shoot and root fresh and dry weights, respectively, than those of the AT treatment of 20°C with a RZT of 20°C (Fig. 2A-2D). The number of leaves, the crown diameter, and the shoot area showed similar patterns (Fig. 2E-2G). No significant interaction effects between AT and RZT on the growth characteristics were observed (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Fresh and dry weights of shoots (A and C) and roots (B and D), number of leaves (E), crown diameter (F), and shoot area (G) grown under AT (subscript, A) and RZT (subscript, R) treatments for four weeks after transplanting. Here, * and ** indicate significance, respectively, at p < 0.05 and 0.01. NS denotes no significant difference (n = 10).

Table 2.

Two-way ANOVA results of measurements for shoot and root fresh weights (FW) and dry weight (DW), number of leaves (No. of leaves), shoot area, and crown diameter of coastal glehnia treated with AT and RZT for four weeks after transplanting

| Shoot FW | Shoot DW | Root FW | Root DW | No. of leaves | Shoot area | Crown diameter | |

| AT (A) | ** | ** | * | * | * | ** | *** |

| RZT (B) | * | NS | NS | NS | * | * | NS |

| A × B | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Photosynthetic and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

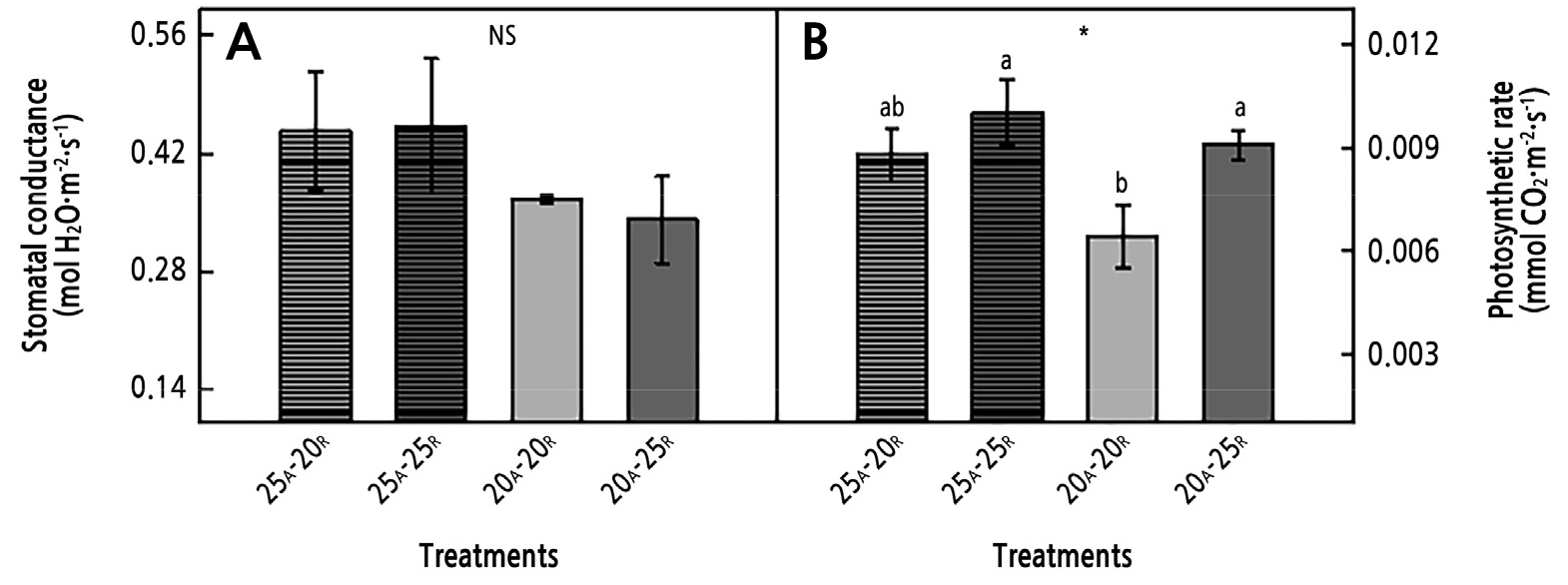

In study II, the photosynthetic parameters (stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rate) and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Fv/Fm, rETR, NPQ, and QY) were measured four weeks after transplanting (Figs. 3 and 4). The photosynthetic rate showed a trend similar to that found in the growth results. The AT of 25°C tended to increase the rate of photosynthesis compared to the AT of 20°C, and the rate at the RZT of 25°C was significantly higher than that at the RZT of 20°C (Fig. 3B and Table 3). The photosynthetic rate at the AT of 25°C with the RZT of 25°C was 1.6 times higher than that at the AT of 20°C with the RZT of 20°C. There were no significant differences in stomatal conductance among the treatments.

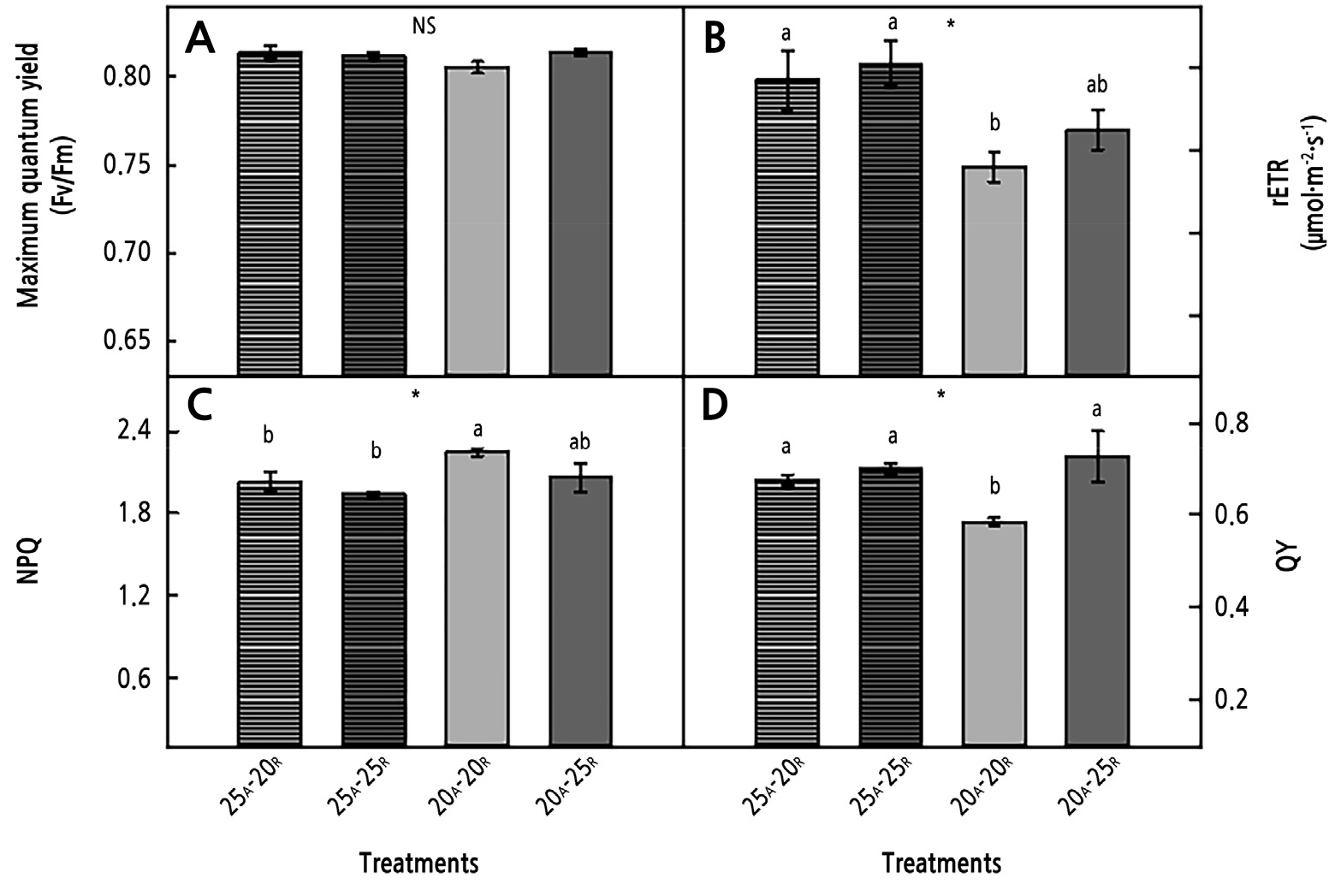

The Fv/Fm ratios did not differ significantly among the AT and RZT treatments (Fig. 4A). The rETR and NPQ outcomes were significantly different between the AT 20°C and AT 25°C treatments (Fig. 4B, 4C, and Table 3). There was a significant difference in QY between the RZTs of 20°C and 25°C, similar to the photosynthetic rate results. The AT 20°C/RZT 20°C treatment showed the lowest values of rETR and QY, though this treatment also showed a high NPQ value (Fig. 4B-4D).

Fig. 4.

Maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm) (A), relative electron transport rate (rETR) (B), non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) (C), and quantum yield (QY) of PSⅡ (D) of coastal glehnia grown under AT (subscript, A) and RZT (subscript, R) treatments for four weeks after transplanting. Here, * indicates significance at p < 0.05, and NS denotes no significant difference (n = 4).

Table 3.

Two-way ANOVA results of measurements for photosynthetic and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of coastal glehnia treated with AT and RZT for four weeks after transplanting

| Photosynthetic parameters | Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters | ||||||

| Stomatal conductance | Photosynthetic rate | Fv/Fm | NPQ | rETR | QY | ||

| AT (A) | NS | NS | NS | * | ** | NS | |

| RZT (B) | NS | * | NS | NS | NS | * | |

| A × B | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

Table 4.

Two-way ANOVA results of mineral contents of coastal glehnia treated with AT and RZT for four weeks after transplanting

| Treatment | Mineral contents | |||||||||||||

| AT (°C) | RZT (°C) | mg·g-1 | mg·plant-1 | |||||||||||

| P | K | S | Mg | Ca | Fe | P | K | S | Mg | Ca | Fe | |||

| 20 | 20 | 65.92 | 25.05 | 43.06 | 2.35 | 11.1 | 0.19a | 4.82b | 2.01b | 3.22b | 0.18b | 0.9b | 0.01b | |

| 25 | 49.61 | 21.46 | 42.05 | 1.9 | 8.57 | 0.08b | 5.61b | 2.39b | 4.64b | 0.21b | 1.0b | 0.01b | ||

| 25 | 20 | 44.42 | 18.94 | 36.78 | 1.66 | 8.21 | 0.07b | 7.68ab | 3.2ab | 5.44b | 0.26ab | 1.26ab | 0.01b | |

| 25 | 67.39 | 25.85 | 53.2 | 2.15 | 10.1 | 0.11ab | 13.1a | 4.97a | 10.3a | 0.42a | 1.99a | 0.02a | ||

| AT (A) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | * | ||

| RZT (B) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ** | * | NS | NS | ||

| A × B | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

Mineral Content

To investigate the growth potential of coastal glehnia seedlings, the contents of several minerals (P, K, S, Mg, Ca, and Fe) were measured (Table 4). Although there were no differences in the P, K, S, Mg, and Ca contents per gram, the AT 25°C/RZT 25°C treatment showed higher contents of P, K, and S per gram than the other treatments. Likewise, the AT 25°C/RZT 25°C treatment led to the highest measured mineral contents per plant compared to the other treatments, with outcomes remarkably higher than those from the AT 20°C/RZT 20°C treatment.

Discussion

Compared to non-aeration, the root zone aeration treatment led to no significant difference in the growth of coastal glehnia seedlings (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The average dissolved oxygen (DO) values in the aeration and non-aeration treatments were 9 and 6.5 mg·L-1, respectively, with a difference of 2.5 mg·L-1. Asao et al. (1999) used DO in a hydroponic system for 6 h (1.7–3.1 ppm) and 24 h (5.0–7.5 ppm) to treat cucumber seedlings; their difference of 3.3–4.4 mg·L-1 did not affect the vegetative growth, but the length of the primary lateral branch decreased in the low DO treatment. In the present study, the difference in the DO content was likely not sufficient to induce growth differences in the coastal glehnia seedlings.

The shoot fresh and dry weights and the shoot area increased as the RZT was increased, and the seedlings under the RZT 25°C treatment showed the highest values (Fig. 1 and Table 1). RZT is a critical physical environment factor that affects seedling root development, water, and nutrient uptake, as well as the biosynthesis of metabolites (Wilcox and Pfeiffer, 1990). Stoltzfus et al. (1998) reported that the shoot fresh and dry weights were high at RZTs of 25–35°C depending on the size (large and small) of musk melon, with the mineral content and plant dry weight rapidly decreasing at RZTs above 35°C due to the limited water uptake rate and reduced mineral transport to the shoots. Compared to RZTs of 10, 20, 26, and 35°C, the RZT of 20°C was shown to improve growth and camptothecin accumulation in Ophiorrhiza pumila, a medicinal plant (Lee et al., 2020). Karnoutsos et al. (2021) investigated the effect of the RZT during the summer and winter seasons in a greenhouse without thermal control on the production of rocket and baby lettuce. Compared to the control and winter (AT approximately 8–24°C) seasons, in the summer season (ca. 26–43°C of AT), the cooled RZT condition (approximately 21.9°C) improved the production yields of rocket and baby lettuce by 18.9% and 31.4%, respectively. The treatment with a RZT of approximately 11–17°C, 3–4°C higher than the control treatment, increased the production yields of rocket and baby lettuce by 15.1% and 16.3%, respectively, compared to the control. This highlights the importance of RZT control in non-ideal AT environments.

Murai-Hatano et al. (2008) suggested that the root hydraulic conductivity increases when the RZT ranges from 10°C to 35°C and is manipulated by aquaporin activity. A high RZT treatment of coastal glehnia most likely stimulated water and nutrient uptake levels, increased root hydraulic conductivity and aquaporin activity, and promoted growth and development, as evidence by the photosynthetic rate and mineral contents (Fig. 3 and Table 4).

In study II, plant growth was affected by different shoot and root temperature combinations. In general, the optimum temperature of the shoot is higher than that of the root zone (Xu and Huang, 2000). Karlsen (1980) reported that the most suitable conditions for the growth of cucumber seedlings were an AT of 30°C with a RZT of 25°C among AT treatments of 15, 20, 25, and 30°C and RZTs of 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35°C. However, Carotti et al. (2021) reported that the light use efficiency of lettuce was higher at an AT of 24°C and a RZT of 28°C compared to the treatment combinations of ATs and RZTs of 20, 24, 28, and 32°C. Therefore, the optimal AT and RZT combination depends on the plant species and growth stage, and an improper temperature combination can cause a metabolic imbalance, ultimately inhibiting biomass accumulation (Thompson et al., 1998). In particular, the carbon reaction of photosynthesis using ATP and NADPH generated by the light-dependent reaction during photosynthesis is carried out through an enzyme-catalyzed reaction, therefore, the Calvin– Benson cycle operates well in plants under proper environmental conditions, including proper temperature conditions (Taiz et al., 2018). In this study, coastal glehnia seedling growth was significantly increased at the AT and RZT of 25°C compared to that when these factors were set to 20°C (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The AT of 25°C may activate the Calvin-Benson cycle more efficiently than the AT of 20°C. The photosynthetic rate of coastal glehnia leaves increased at ATs of 15–25°C and decreased at an AT of 30°C, and the transpiration rate was lower than that at an AT of 25°C (data not shown). This implies that temperature conditions above 25°C result in the inhibition of photosynthesis by inducing heat stress, which can negatively affect the growth and development of coastal glehnia seedlings. In addition, the crown, located at the borderline between the shoot and root, is the growing point for new leaves of coastal glehnia and plays an important role in transporting minerals and water from the roots to the shoots. Therefore, the RZT of 25°C improved the growth and mineral contents of seedlings compared to the RZT of 20°C due to the active absorption of water and nutrients in the root zone as well as the active photosynthesis reaction by indirectly heating the crown of coastal glehnia (Figs. 2, 3, 4 and Table 4). Both root zone and crown heating have already been applied in greenhouse cultivation systems, and in the winter season, such treatments have been found to increase the absorption of nutrients by strawberries, cucumbers, and tomatoes (Choi et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2010; Sato and Kitajima, 2010; Kwon et al., 2019), resulting in improved growth.

When plants are stressed by excessive light energy or other environmental factors, the photoprotective mechanism is activated to release excess energy by the emission of light energy via photochemistry, fluorescence, and heat (NPQ). Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters are affected by the temperature due to the structure and function of the thylakoid membrane (Janssen et al., 1992). However, in the present study, a temperature treatment was not sufficient to induce stress in coastal glehnia seedlings. One of the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, the Fv/Fm values, was similar among the treatments, but the AT and RZT of 20°C led to decreased QY and rETR outcomes with an increase in NPQ compared to the other treatments (Fig. 4). It was confirmed that the AT and RZT of 20°C led to the emission of more heat from excessive light than the AT and RZT of 25°C, and the plants’ ability to use light photochemically with the former treatment was lower than that under the latter treatment.

In conclusion, AT and RZT were found to be closely related to the growth performance of coastal glehnia seedlings. The optimal combination of temperature conditions during the seedling stage promoted the growth and development of high-vigor seedlings of coastal glehnia. The combination of an AT of 25°C and a RZT of 25°C effectively enhanced the growth of coastal glehnia seedlings via improved photosynthesis and mineral uptake. These results can be used to develop cultivation strategies for coastal glehnia production in controlled-environment plant production systems, such as PFALs or greenhouses.